UNSW Study Reveals HFO Refrigerants Can Break Down into Greenhouse Pollutants

Scientists at the University of New South Wales (UNSW) have found that hydrofluoroolefins (HFOs), widely used as refrigerants and aerosol propellants, can partially decompose into persistent greenhouse gas pollutants, including fluoroform - an HFC with a global warming potential more than 14,000 times greater than CO₂.

A study led by Dr. Christopher Hansen from UNSW Chemistry, published in the Journal of the American Chemical Society, demonstrates that some HFOs break down into small amounts of fluoroform under atmospheric conditions. This discovery challenges previous assumptions about the environmental safety of HFOs, which have been promoted as low-impact alternatives to ozone-depleting substances.

“We don’t fully understand the environmental impacts of HFOs at this point,” says Dr. Hansen. “But, unlike previous examples such as the CFCs and leaded petrol, we are trying to figure out the consequences of large-scale emission before we’ve potentially harmed the environment and human health in an irreversible way.”

Investigating the Breakdown of HFOs

HFOs have been adopted as replacements for hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), which were phased out due to their high greenhouse warming potential. While HFOs have a shorter atmospheric lifetime, their decomposition pathways have been a topic of debate.

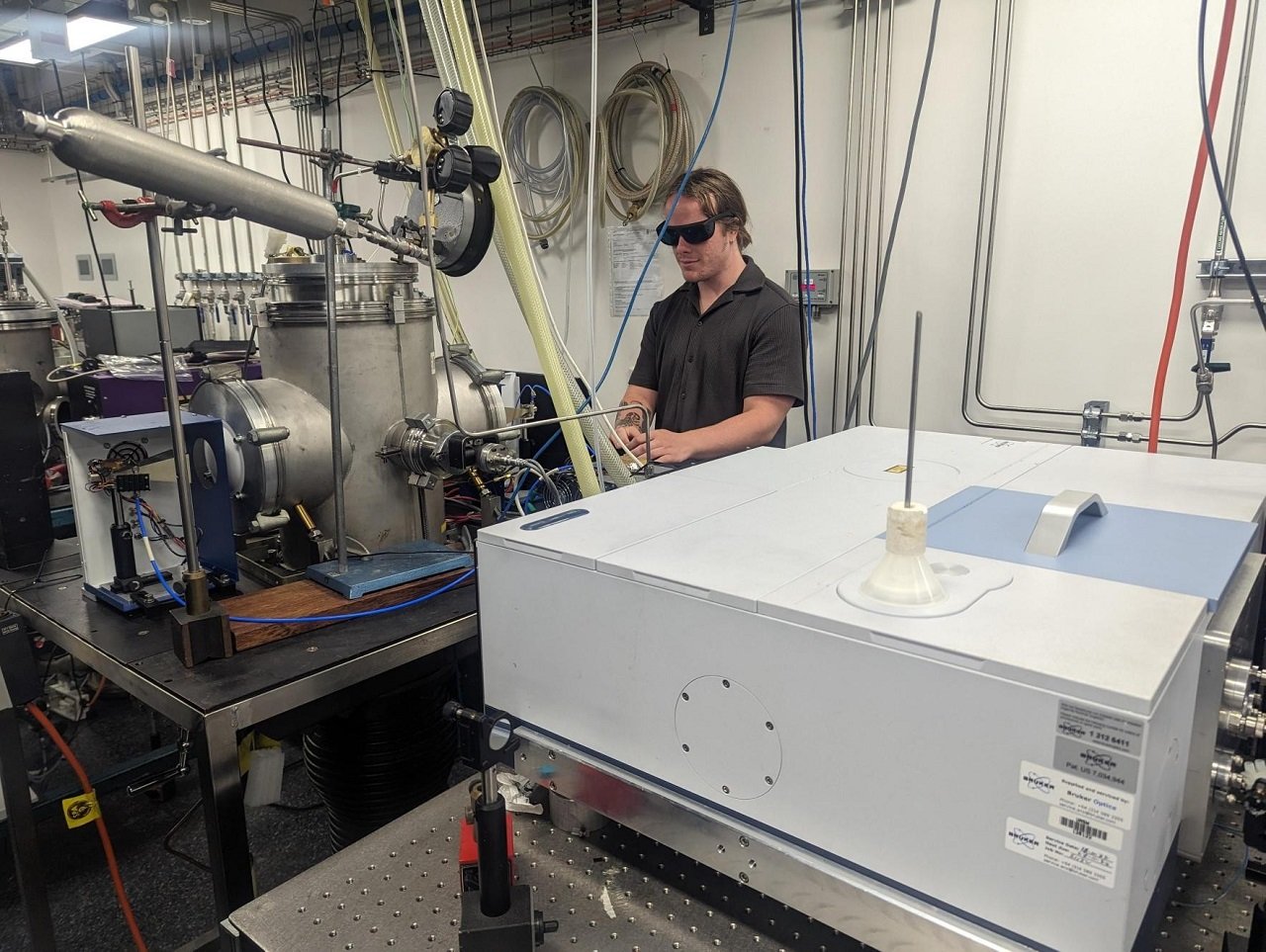

Dr. Hansen’s team used advanced spectroscopy and a gas mixture at various pressures to simulate atmospheric conditions. Their experiments confirmed that when HFOs break down, they initially form trifluoroacetaldehyde, which can then transform into fluoroform under sunlight exposure.

Although fluoroform is produced in small quantities, its long atmospheric lifetime - up to 200 years - means even minor emissions could have a significant impact. “We have demonstrated comprehensively that some of the most important HFOs do break down into HFCs and have provided the first hard scientific data needed to model and predict the consequences of large-scale emission,” says Dr. Hansen.

Implications for Climate Modeling

The findings provide new data for climate models and raise questions about the long-term sustainability of HFO use. “Many atmospheric crises have caught us by surprise,” says Dr. Hansen, referencing historical environmental issues like the ozone hole and leaded petrol. “But this wasn’t because our models were not good enough, but rather because the important chemistry was missing from the models.”

With this study, scientists now have the data needed to incorporate HFO decomposition into climate predictions. Researchers at UNSW and beyond are preparing to analyze how continued HFO use could impact global warming.

Dr. Hansen and his team plan further experiments to investigate the effect of different wavelengths of light on the breakdown process. “For this paper, we performed the experiments at a single wavelength, the one currently used in regulatory studies,” he says. “We plan to study this chemistry using other wavelengths, where the yield could be higher or lower.”

These findings highlight the need for ongoing evaluation of synthetic refrigerants and their environmental impact before widespread adoption.